|

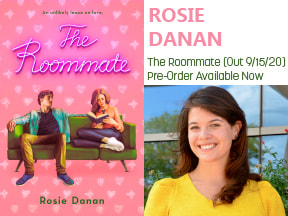

Romance writers are proud of many things related to our craft: character development, humor, snappy dialogue, and steamy love scenes. There's something else, though. We're proud of our GIF game! Meet some up and coming authors' romance novels as described by the authors in GIFs. The authors from vol. 1 of The Gif of a Happily Ever After nominated these authors whose books we can't wait to see in print.  Hot Copy by Ruby Barrett Rosie Danan, author of The Roommate (available 9/15/20), suggested Ruby. Learn more about Ruby here.  Rules of Engagement by Natalie Caña Denise Williams-Klotz, author of How To Fail At Flirting (available 12/1/20), suggested Natalie. Learn more about Natalie here.  Standing But Not Operating by Jenny Howe Suzanne Park, author of Loathe At First Sight, suggested Jenny's work. Learn more about Jenny here.  To Be Your Last by Rae Kennedy (Avail. 6/26) Allison Ashley, author of Perfect Distraction, suggested Rae. Learn more about Rae here.  Storysinger by Lindsay Landgraf Hess Katie Golding, author of Fearless (available 7/28/20), suggested Lindsay. Learn more about Lindsay here.  Sweet Victory by Tara Martin Janet Walden-West, author of Salt + Stilettos (available 4/21/20), suggested Tara. Learn more about Tara here.

4 Comments

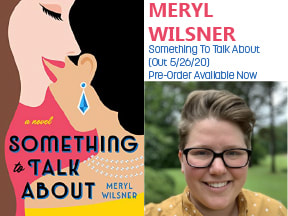

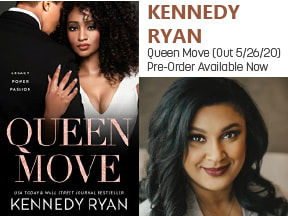

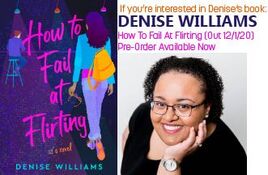

Spring 2020 continues to show us the human capacity for care and resilience, and, it seems, there's no better time to think critically about our genre and the world around us than when we're in the middle of so much turmoil. If you've joined us for #2020RomClass, you've heard from our wonderful guest speakers. Consider supporting them by pre-ordering their upcoming books. I've loved co-facilitating Moving Past Bodice Ripping Toward Shredding The Patriarchy: Romance Novels and Tools for Justice. If you're interested in my debut novel, How To Fail At Flirting (available 12/1/20), click here.

Moving Past Bodice Ripping Toward Shredding the Patriarchy: Romance Novels as Tools for Justice has a guest instructor this week! Rosie Danan, author of The Roommate (coming 9.15.20 from Berkley) is talking about the stigma of female desire.  Rosie Danan Rosie Danan I’ve spent a lot of time exploring the ways in which societal stigma against female sexuality intersects with both internal shame and external scorn in regards to reading and writing romance novels. Before I begin my analysis, I want to acknowledge that any type of sexuality that falls outside of the allo-cis-het-male gaze receives a degree of othering from mainstream media and society at large. In fact, too often, the breadth of the romance genre is minimized as books “by and for women,” when there are many writers and readers who fall outside of that binary definition. All of that said, I think there is a specific case to be made about the ways in which American society in particular polices female desire, and the impact that misogyny has on people who perpetuate and internalize viewpoints developed to uphold and further patriarchal power structures. I have experienced a spectrum of scorn and shaming of my romance reading, and later writing, across the span of my lifetime in a pattern that I believe many romance readers will recognize either in part or as a whole. When I was a teenager and started reading romance I was told it was inappropriate by my father and so I felt like I was doing something elicit by reading them. Thus, for over a decade, romance novels became something I felt I had to hide. This makes me so sad in hindsight, because in many ways I can’t think of a better time for romance reading than when you’re trying to understand relationship dynamics, desire, and agency. It wasn’t until the emergence of e-readers, a more covert platform for consumption, that I really leaned into my romance novel hobby, turning it from the occasional purchase to a weekly indulgence. When I was in my early twenties, the romance genre underwent the beginning of a rebranding: from bodice-rippers to feminist art. Female focused online communities such as Jezebel.com lead the charge in highlighting both the work and genre commentary of writers such as Sarah MacLean, Eloisa James, and Lisa Kleypas. The rebrand made it easier to reconcile my affection for romance novels with the rest of my burgeoning identity. At the time, I was using dating apps like Tinder and Hinge to meet men of the same age. During first or second date small talk, I often tossed out my passion for reading romance novels and the fact that I’d started writing one. I received indulgent smiles or awkward chuckles in return but later, the same men told me that romance novels didn’t count as “real books,” and I found myself reluctantly rounding out my bookshelves with Faulkner and James Joyce—books that sat untouched and glowering behind neat leather spines. Now, as I move into my thirties, I’m fortunate to have those days of dating jerks behind me. I’ve settled firmly into the romance community at large in on- and offline writing groups, but just this year I experienced harassment at work from both male and female coworkers when they found out I write and read “dirty books,” to the point that I have no returned to actively hiding my publishing success from my corporate peers.  In summary, I spent decades trying to unlearn the shame associated with my romance reading and writing—to recognize that the books I love are both important and inherently worth—only to find that reconciling my identity as a romance writer and a respected female business leader is very much still a work in progress. When the cycle of scorn associated with romance seems endless, I think of the stereotypical romance audience. The ones for which the derisive genre shorthand “mommy porn” was named. Are these women, arguably removed from eligibility having shifted from the age-old cultural archetype of “the maiden” to “the mother” the only ones able to claim their reading habits publicly and proudly? Is the perspective of giving birth required to unleash full “f*ck it” mode when it comes to owning our genre affiliation? My first instinct is to ask, how can we encourage younger romance readers to embrace their passion, on and off the page without fear of reproach? But like other patriarchal structures that blame the victim, I realize after further examination that with that technique, we’re starting in the wrong place. We should instead ask ourselves how we can speak to the shamers in our lives on an individual level and encourage them to address their own biases. How many men who consider themselves feminists would still balk at catching their thirteen year old daughter with a book whose cover featured the prominently displayed abdominal muscles of a burly, if often headless, man? How many women who run book clubs would never consider picking a monthly selection with a pink cover? Who exactly does burying art that values female pleasure serve? The answers become a bit more clear when you consider the sorry state of sex in America. A study from the American Sociological review uncovered that the rise of “hook-up culture” has introduced a new double-standard in relationships where “doubts about women’s entitlement to pleasure in casual liaisons keep women from asking to have their desires satisfied and keep men from seeing women as deserving of their attentiveness in hookups.” Women’s Health went on to name the phenomenon The Orgasm Gap. Some of their more startling findings:

Personally, I have processed the dissonance of loving an art form and consistently being told it’s wrong through writing. A key theme of my debut novel THE ROOMMATE is shame and specifically shame around female desire and sexuality. Writing this book was my own exercise in radicalization. My journey of accepting my “unpalatable” passion, followed the journey of a main character, Clara, who is really ashamed of wanting more from sex than what she’s been getting from her previous partners trying to figure out if she’s brave enough to own her dissatisfaction.  All Clara wants in life is to make her family as comfortable as possible. Then she meets this porn star, Josh, who shows her, through ownership of both his profession and sexuality, that she can and should claim agency over her desires. Ultimately, she transcends his advice and not only empowers herself but decides that together they should assist other people in reclaiming their sexual agency at scale. It was very powerful for me to be on this parallel path with my main character: doing something I was afraid of, knowing I almost certainly would encounter scorn from both people who know me and potentially strangers, knowing that the more successful the book becomes, the more people I’m exposing to my rebellion. Romance writers and readers at large, I think, go on a journey in which we say, in whatever way is right for us, that we like not only consuming books about—but also talking about—things like kissing or sex or romance without sex if that’s what you’re moved to portray/consume. In a very pure form, especially in our current climate, I think people want to feel good, they want to enjoy themselves and they’re becoming less afraid to say so without apology. For me, writing about porn as an industry and sex workers, is a metaphor for romance as a genre because both are stigmatized, obviously to different degrees, for portraying desire. It was really important to me to portray a marginalized group appropriately and honestly, but at the same time I think a lot of people who don’t fall into the mainstream, marketable allo-cis-het-white desire can see themselves in THE ROOMMATE. At the end of the day, our society isn’t anti-sex. There’s a certain type of sexuality that’s very mainstream: from The Fast and The Furious movies to Ernest Hemingway. No one is saying it's wrong or shameful to consume that kind of media. No one tells Jonathan Franzen that his books aren't smart or serious because he depicts desire. Though they should tell him that for other reasons. (Don’t @ me Jonathan Franzen). Patriarchy dictates which types of sex we can put on cable and which kind we should hide under our pillows. I’m not ashamed of my book. I’m really proud of THE ROOMMATE and the way it handles desire and furthermore, I think that it’s sexy. It's meant to be sexy. But at the same time, I won’t pretend I’m not still afraid.

We’re fighting an uphill battle, but I believe that every time you read a romance, every time you recommend one to a friend, or proudly check one out from the library, every time you advocate for this genre or support it with your hard-earned money, you’re dismantling power structures that want you to believe that your pleasure doesn’t matter as much as a man’s and that’s pretty f*cking cool. Rosie Danan writes steamy, big-hearted books about the trials and triumphs of modern love. When not writing, she enjoys jogging slowly to fast music, petting other people’s dogs, and competing against herself in rounds of Chopped using the miscellaneous ingredients occupying her fridge. As an American expat living in London, Rosie regularly finds herself borrowing slang that doesn’t belong to her. Learn more about Rosie and The Roommate, available from Berkley September 15, 2020.

|

About DeniseDenise reads romance novels, writes research papers, can be found humming "Baby Shark" long after her toddler has gone to bed, and loves ruining her character's lives but then giving them happily ever afters. She is a member of Romance Writers of America® and a 2019 Golden Heart® Finalist, and her debut novel HOW TO FAIL AT FLIRTING will be out fall 2020 from Berkley. Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed